You don’t exactly feel like you’ve won the lottery when you get cancer.

But that’s how my doctor made it sound, when he called me into his office to discuss the test results for the lump on my right arm, just inside the bend of the elbow. I swear, the old fart—just some quack I found online by searching near my house—had a tinge of actual excitement in his voice as he read off the diagnosis. It was all gibberish to me, words like synovial sarcoma and monophasic epithelial, but then he got to a phrase simple enough for me to latch onto.

“What was that?” I interrupted the stream of medical chatter.

He looked up from the paper and pushed his glasses off the tip of his nose. “I said, ‘this form of growth is rare, occurring in an average of one person per million.’”

“One in a million,” I repeated slowly. A cliché. Something you whispered to your sweetie when you gave her that ring with the obscene diamond. But even though I’d heard and said those words countless times in my life, they suddenly seemed like an entirely new concept. “So you’re telling me there are only about seven thousand people in the entire world who have this kind of cancer?”

The doc smiled at me—smiled, if you can believe it, and Jesus did I want to slap that expression right back off his face—and said, “Actually, it’s probably less than that. There are two possible types of cell growth associated with synovial sarcoma, and it looks like you have them both.”

Wow. Lucky me.

“Am…am I gonna die?” I blurted. The office had begun to spin sickeningly.

He shook his head before the question even left my mouth, the one thing he did right during that entire meeting. “No, absolutely not. This is very treatable, with a seventy-percent recovery rate. Synovial sarcoma is typically slow-moving and attacks soft tissue, starting with the joints.” He gestured toward the swollen place on my arm, a lump about the size of a water-bottle cap. “Yours occurred in a location where amputation won’t even be necessary. So we’ll do surgery immediately to remove the tumor, followed by aggressive chemotherapy to eradicate any remaining cells. As long as it hasn’t spread, we’ll beat this thing.”

Guess what?

It had spread.

The main mass came out of my arm, no problem. My parents wanted to fly down from Pittsburgh, but I told them not to bother. I had naïvely high hopes. The procedure was in-and-out, a day in the hospital. The staff there was overworked, with a constant stream of new patients, and didn’t have time to learn anyone’s name. They called us by our cancer, and so for nearly twenty-four hours my name became Synovial. But at least they said it affectionately.

A week later, back in the doc’s office. Metastization in both lungs and parts of my bowels.

I’d never won so much as a game of bingo in my life, and now here I was, at the age of 24, a grand prize Powerball winner in the cancer lotto.

I spent an afternoon crying, pleading and bargaining with God. And, of course, cursing my luck.

Then the dead decided to get up and start chowing down on the living, and I stopped complaining.

¤

I was headed to my first chemotherapy appointment when the zombies came.

God, that still sounds ridiculous to actually say.

We’d been hearing reports for days. Strange viral outbreaks in multiple countries. Chaos overseas. Warfare on the streets of South America, against what appeared to be animated corpses. No cause, no pattern or rhyme or reason. The laws of reality had simply changed. To tell you the truth, I hadn’t paid much attention; I had more important things on my mind. Plus, it was mostly business as usual in the good ol’ U. S. of A. at this point, which is why I was about to get highly toxic chemicals pumped into my veins that would make my hair fall out and turn my stomach into a sewer, rather than cowering at home with an apartment full of stockpiled provisions like some people.

I had just gotten out of my car when I heard the moaning. Followed by screams. The parking lot for the chemo treatment facility sat on the corner of 7th and Slide, giving me a long view up 7th Avenue, through the middle of tall, downtown building blocks. People were abandoning their cars in the middle of the street, shouting as they pounded the pavement, moving in unison like a herd of frightened sheep. I watched as a cloud of complete pandemonium moved up the road toward me, and tried to figure out what was happening.

And then I saw them: bloody, ragged figures shambling through the crowd, the less decayed ones able to run. They snatched at anything that moved, pulling stragglers down and gathering around to feast. Just fifty yards away, I saw a woman caught by five creatures and dismembered as she screamed. One of them gripped an ankle and walked away with her leg, gnawing into the flesh like it was a chicken wing.

The horror paralyzed me. By the time it broke, one of the things had spotted me and lurched in my direction. It was hideous, a man with part of his forehead caved in so much that one eye was gone and a patch of yellow fungus was visible on his chest through a tattered shirt. I wheeled around to run, but it grabbed my shoulder and tossed me back against the door of my car.

It moved in, jaw open to take a bite out of my throat. The teeth in that maw were black, jagged stumps. I pressed back against the car.

The zombie paused just inches from my skin. Its one good eye roamed across me, as though evaluating. I thought its nostrils flared.

Then it turned, forgetting about me, and leapt on a fleeing cop.

I stood still for a long moment as chaos boiled around me, waiting for it to come back, but it never did. Neither did any of the others.

In all the zombie movies and literature, no one ever mentioned that their food might have an expiration date also. But I guess it made sense, even then.

Why would these things want to eat something whose guts were as rotten as their own?

I got back into my car, curled up in the seat, and stayed there well after night had fallen, and the city was a graveyard.

¤

It spread—metastasized—fast. Phones went first, followed by television, electricity, and then radio. The nation was overtaken in days. I never even found out what happened to my parents. Zombies roamed the streets, hunting down the last of the living. They busted through my neighbors’ doors without any provocation, as if they could sense the people cowering inside, and devoured them. The leftovers got up and joined the crusade.

But they never even looked my way.

Lucky me.

¤

Three months later, a car horn honked outside my building, the way it did every Tuesday and Thursday. I grabbed my wallet and keys—a habit leftover from the days before the world went to Hell—and walked out my front door.

Two zombies loitered on my doorstep, staring vacantly at the brick wall of the building. One of them—a woman that had probably been a hot little number before her nose and cheeks were chewed off and the rest of her began to decompose—had been hanging around my neighborhood for weeks. I shouldered them aside so I could get past, eliciting a plaintive groan from the female.

“’Scuse me, folks,” I muttered. They stumbled a few steps away and then resettled.

A yellow Ferrari 458 idled at the curb in front of my building. I hurried out and opened the passenger door. Behind the wheel sat a middle-aged guy wearing a tie-dyed scarf over his slick, bald head.

“What’s up, Synovial?” he greeted me.

“Not much, Esophageal.” I patted the Ferrari’s rear panel. “New ride?”

“Yes sir. Found it down at the police impound. Hurry up and get in. You know how tight Doc Lymphoma likes to keep the schedule.”

I climbed inside the vehicle and we raced down the deserted streets. And by ‘deserted,’ I mean ‘free of the living.’ Zombies were still everywhere, lining the sidewalks, loitering on the street corners, wandering into the road so that every few minutes Esophageal would have to dodge around a walking corpse or else really mess up the hood of his car. After eating every human being they could find, they just sort of…wound down. Became docile. They would shamble around listlessly and then come to a stop somewhere for a few hours before waking up and moving on.

Now they were all the population the city had left; the living dead.

And us, of course.

The dead living.

Spoiled entrées.

They left us alone, and we returned the favor.

With the way Esophageal drove, it took only twenty minutes to reach the chemo facility. By now, we knew which roads were still clogged with abandoned cars and planned our routes accordingly. He left the keys on the seat as we went into the building.

A few friendly faces called out greetings in the sunlit waiting room. But there were also a lot of folks I didn’t know; more and more cancer patients arrived in the city everyday, as word of our setup got around. I denied the urge to stop and talk to Ductal Carcinoma, who had worn an extra-short skirt today. Doc Lymphoma stood by the entrance doors to the rear of the facility, and he looked pissed.

“You’re late,” he growled. “I almost gave away your chairs.”

“Sorry,” we apologized.

Doc Lymphoma was a tiny, white-haired man in his sixties, at least a foot shorter than me, but he could intimidate better than a seven-foot linebacker. He’d been a podiatrist once upon a time, until being diagnosed with what he called his ‘constant companion.’ Determined not to waste his remaining time with treatments, he sold his practice, retired, and prepared for a few precious last years of fishing and beer. The world ended before he could even get to the lake. I liked him much better than my previous doctor.

The fluorescents were on in the back of the clinic, along with some industrial box fans to keep the air cool and circulating. This was the only place I saw electricity anymore. Doc Lymphoma had organized teams to find and bring back every generator in the city, along with enough fuel to keep them running for ten years.

Far longer than the chemo drugs—and probably most of us—would last.

We followed Doc Lymphoma to a room with five leather easy chairs clustered in a semi-circle. Our usual Tuesday/Thursday 2PM crew was already present and hooked up to their IV’s: Squamous Cell, Pancreatic, and Osteosarcoma. I settled into a recliner between Esophageal and Osteosarcoma and waited while Doc inserted the needle in my arm.

Once we were all hooked up and the medication was flowing, he stood in front of us and said, “As always, I caution you—”

We finished his chant in unison: “‘You are not an expert in this field, and the treatment may very well kill us. You accept no responsibility in the case of our deaths.’”

“Damn right,” he grumbled, before walking out of the room.

Doc Lymphoma was not a surgeon, and he’d never administered chemotherapy in his life before the zombies, but he was the only medical professional we had. After getting the clinic up and running and gathering all of us together, he’d been able to do enough research to be sure how much of a dose would be lethal. Whether the amount he gave us actually helped our individual diseases was another question entirely. He had no equipment to run tests on us, and wouldn’t know how to use it if he did. I asked him once how we would know if we ever went into remission, and he said, “Well…I guess you won’t die now, will you?”

The five of us sat in silence for a few seconds, settling into our chairs. After a few weeks of treatment, my stomach started churning almost as soon as the drugs hit my bloodstream. I shut my eyes against the creeping nausea.

“Did you hear about Glioma?” Pancreatic asked. He was rail thin, with bruised purple hollows under both eyes. He’d lost so much weight in the short time I’d known him, he almost seemed to be evaporating.

“Which one?” Esophageal asked.

“Two. The one with the bum knee.”

“Oh yeah. What about him?”

“Died. Last week. Organs started shutting down one after another, just boom boom boom, like dominoes. Doc gave him enough morphine to play him out peacefully.” Pancreatic sighed. “There but for the grace of God, huh?”

From the far end of our sewing circle, Squamous Cell snorted. “I got a feelin’ God’s grace is gonna get you there sooner or later, my friend.”

Esophageal laughed.

Beside me, Osteosarcoma had been unusually quiet. I nudged his arm. “Hey man, you okay?”

He started to nod, then bent over and grabbed for the trash can that sat beside each of our chairs. He pulled it into his lap, dunked his head inside. A second later, the guttural sounds of regurgitation drifted out.

Pancreatic turned his gaunt face away. “Damn it, I can’t look at that or I’ll start.”

We gave Osteosarcoma some privacy to finish up. When he leaned back, his face was as green as a Granny Smith. “S-sorry. Sorry, I…” He didn’t finish, just closed his eyes and swallowed.

A thought went through my head and came out of my mouth before I could filter it. “You ever wonder why we go through this? We’re all miserable and sick all the time. I mean…what’s the point?”

“To live,” Esophageal answered. “I wanna live. Don’t you wanna live?”

“I guess.”

“You guess? That’s no answer, Synovial. You gotta have a positive attitude, or the chemo won’t do anything for you.”

“Yeah, but don’t you ever ask yourself…what do we have to live for anyway? Everybody else in the whole goddamn world’s been eaten, for Christ’s sake.”

Squamous Cell held up a finger. “Don’t kid yourself, bucko. We’re still being eaten, just not by any fuckin’ zombie.”

“Look.” Esophageal twisted in his recliner to look at me, moving IV tubes out from between us. “The fact of the matter is, we are the lucky ones in all this. We’ve been given a reprieve that none of the healthies got. If we just lie down and wait for the cancer to kill us…well, we’re just throwing that reprieve away.” He poked me in the chest. “Remember that.”

I did. I thought about what he’d said a lot over the next few days.

And for the first time, I began to feel like I really did win the lottery.

¤

Several weeks later, Esophageal and I went on a food run, to replenish the supplies at the clinic. All the grocery stores in the city were still chock-full of canned goods and non-perishables. With the meager appetites that most of us had left, it would last a while.

In the dark canned goods aisle, Esophageal suddenly wheeled his cart around and headed for the front of the store. “Be right back. I wanna see if they got any of those little chocolate donuts that aren’t too expired.”

After he left, I continued on, around the corner. Further up the next aisle, a lone zombie stood perfectly still, face inches away from the bottles of cooking oil, as though reading ingredients. There seemed to be a lot less of them hanging around these days. Pancreatic said they were migrating to look for new food sources. I pushed my cart toward this one, meaning to pass by to get to the coffee tins.

When I was still a few feet away, the zombie performed a slow, ponderous turn.

Two dull, crusted eyes found me. Its nostrils quivered as its upper lip peeled back in a snarl.

Looks like Doc Lymphoma was wrong. There was another way to tell when we went into remission.

Lucky me.

Russell C. Connor has been writing about demons, serial killers, and the end of the world since he was five years old. His short work has appeared in Black Petals Magazine, Alien Skin, and Sanitarium, among others. He currently has eleven novels available, including the supernatural crime-noir novels Finding Misery and Whitney, about hurricane survivors facing a deadly plague and a ravenous beast. His 2015 novel, Good Neighbors, won the Silver medal for Horror in the 2016 Independent Publishing Awards, and his newest novel, Through the Dark Forest (The Dark Filament Ephemeris, Book 1) was released in October 2016. He lives in Grand Prairie, TX with his mistress of the dark, demonspawn daughter, rabid dogs, and extensive movie collection, and has been a member of the DFW Writers’ Workshop for 9 years.

Russell C. Connor has been writing about demons, serial killers, and the end of the world since he was five years old. His short work has appeared in Black Petals Magazine, Alien Skin, and Sanitarium, among others. He currently has eleven novels available, including the supernatural crime-noir novels Finding Misery and Whitney, about hurricane survivors facing a deadly plague and a ravenous beast. His 2015 novel, Good Neighbors, won the Silver medal for Horror in the 2016 Independent Publishing Awards, and his newest novel, Through the Dark Forest (The Dark Filament Ephemeris, Book 1) was released in October 2016. He lives in Grand Prairie, TX with his mistress of the dark, demonspawn daughter, rabid dogs, and extensive movie collection, and has been a member of the DFW Writers’ Workshop for 9 years.

Russell C. Connor’s Amazon author’s page: https://www.amazon.com/Russell-C-Connor/e/B009OK36YY

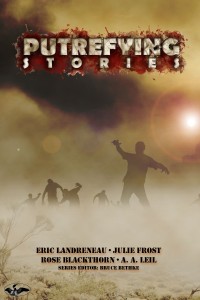

If you enjoyed this story, be sure to check out PUTREFYING STORIES, just $0.99 for Amazon Kindle or free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers!

If you enjoyed this story, be sure to check out PUTREFYING STORIES, just $0.99 for Amazon Kindle or free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers!

Link: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B017A5IF86

Commenting is currently disabled. Sorry about that, but even with the best filtering software we could buy, SHOWCASE was still averaging about 250 spam comments daily, and moderating the comments had become a nightmare. We hope to find a solution to this and re-enable commenting soon, but until we do, we invite you to comment on this story at facebook.com/stupefyingstories.